More Information

Submitted: 10 October 2020 | Approved: 13 November 2020 | Published: 16 November 2020

How to cite this article: Sosa M, Cardinal P, Elizagoyen E, Rodríguez G, Arce S, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 lockdown: A comparative study (before and during isolation) on the 9 de Julio city (Buenos Aires, Argentina) population. Arch Food Nutr Sci. 2020; 4: 020-024.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.afns.1001023

Copyright License: © 2020 Sosa M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: COVID-19 lockdown; Eating habits; Lifestyle; Online survey

Eating habits and lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 lockdown: A comparative study (before and during isolation) on the 9 de Julio city (Buenos Aires, Argentina) population

Miriam Sosa1,2*, Paula Cardinal1,3, Eliana Elizagoyen1,2, Graciela Rodríguez1,3, Soledad Arce1, M Fernanda Gugole Ottaviano1,3, Victoria Pieroni1,2 and Lorena Garitta1,2

1Department of Food Sensory Evaluation (DESA, Higher Experimental Institute of Food Technology (ISETA), 9 de Julio, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET), Argentina

3Scientific Research Commission of the province of Buenos Aires (CIC), Argentina

*Address for Correspondence: Miriam Sosa, Department of Food Sensory Evaluation (DESA), Higher Experimental Institute of Food Technology (ISETA), 9 de Julio, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Email: [email protected]

Following the COVID-19 proliferation beyond China’s borders at the beginning of 2020, containment measures have been taken by different countries around the globe. Citizens were forced to stay at home. Specifically, on March 19th, the Argentine Government decided to implement the “Social, preventive and mandatory isolation”, strategy that unfortunately impacts on the lifestyle, the practise of physical activity and on the nutritional aspect of the population. The aim of this study was analize eating habits and lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 lockdown on the 9 de Julio city, Bs. As., Argentina. The survey was conducted using Google Form. The questionnaire was divided into different sections: sociodemographic data, eating habits, physical activity and concepts and emotions associated with isolation. The research reached 287 responses with a medium socioeconomic level. During isolation, the frequency of purchases decreased. It was observed an increase in the consumption of pasta, bread and cakes. Concerning the physical activity, approximately 70% declared to train before the COVID-19 lockdown, decreased by 13% during the lockdown. Other activities conducted during the COVID-19 lockdown; the most mentioned were cleaning the house, cooking, watching television, series and movies. A percentage greater than 50% of the surveyed population associated the situation of lockdown with positive emotions (share with my family, stay at home); while only 24% associate it with negative emotions (anxiety, anguish, fear). It is expected that most habits will return to normal, however, it would be interesting to know which of those developed, adopted and implemented during lockdown will remain in the new normality.

Following the COVID-19 proliferation beyond China’s borders at the beginning of 2020, containment measures have been taken by different countries around the globe. Citizens were forced to stay at home [1]. On March 11th 2020, the World Health Organization declared a state of a pandemic and specifically, on March 19th the Argentine Government decided to implement the “Social, preventive and mandatory isolation,” strategy that unfortunately impacts on the lifestyle, the practice of physical activity and on the nutritional aspect of the population [2]. In this sense, note that, although nutrition plays an important role in our physical and physiological health, it also represents an everyday aspect that allows socialization and, in some cases, it is a regulatory mechanism of psychological situations over which there is no control [3,4].

The main research response for COVID-19 has been related to the understanding of the virus, its spread, and health consequences; however, not only health is being affected [5]. Consumers’ concerns and their uncertainty about this pandemic’s extent affect in particular eating habits and everyday behaviours.

In turn, the population can experience various negative emotions that can contribute to altering food consumption, involving emotional aspects (intense desire to eat), behavioral (looking for food) and cognitive (thoughts related to food), among others [2,6].

The main aim of the study was to focus on the first impact of a health crisis on consumers’ behaviour regarding eating habits and lifestyle changes a small population (50.000 inhabitants) far from the big urban centres.

Survey methodology

The project was carried out by ISETA researchers using a web-survey to obtain data about people eating habits and lifestyle during the COVID-19 lockdown. The survey was carried out in the 9 de Julio city, a small city located in the Buenos Aires province, Argentina.

The survey was conducted the first half of May by using an online platform accessible through any device with an Internet connection. The survey was disseminated through social networks (Facebook, WhatsApp), and mailing lists. This method of administration provides a statistical collective whose population parameters cannot be controlled as it is the case for probabilistic sampling. However, it was completely effective for the research objectives because it facilitated the wide dissemination of the survey questionnaire during a period where, due to the pandemic, there are many restrictions.

The questionnaire was specifically built using Google Form. It included 78 questions; divided in different sections: sociodemographic data, eating habits, physical activity and concepts and emotions associated with isolation.

All participants were fully informed about the study requirements and were required to accept the data sharing and privacy policy before participating in the study. Participants completed the questionnaire directly connected to the Google platform. Participants’ personal information, including names was anonymised to maintain and protect confidentiality. The anonymous nature of the web-survey does not allow tracing in any way sensitive personal data. Therefore, this web-survey study does not require approval by the Ethics Committee.

Once completed, each questionnaire was transmitted to the Google platform and the final database was downloaded as a Microsoft® Excel® sheet.

Statistical analyses

The data corresponding to the closed option questions were counted and taken to percentages.

The data corresponding to open questions were qualitatively analyzed. A search for recurrent sentence was performed, grouping different expressions for the same sentence in one category (i.e. “I should work,” “the economic situation is complicated” and “it generates financial insecurity” grouped as economic concern).

Statistical analysis was performed using Genstat statistical package (VSN International Ltd., Hampstead, UK) and Microsoft® Excel® 2010.

Sociodemographic data

The research reached 287 responses with a medium socioeconomic level. The age range of the respondents was 20 to 70 years, with a mean age of 41 years. 82% of the surveys were carried out by women and 80% had completed high school. Regarding children less than 18 years of age who lived in the households of the respondents, there were 36% who said they did not live with children of this age, while a higher percentage of the respondents (55%) lived with 1 or 2 children under 18.

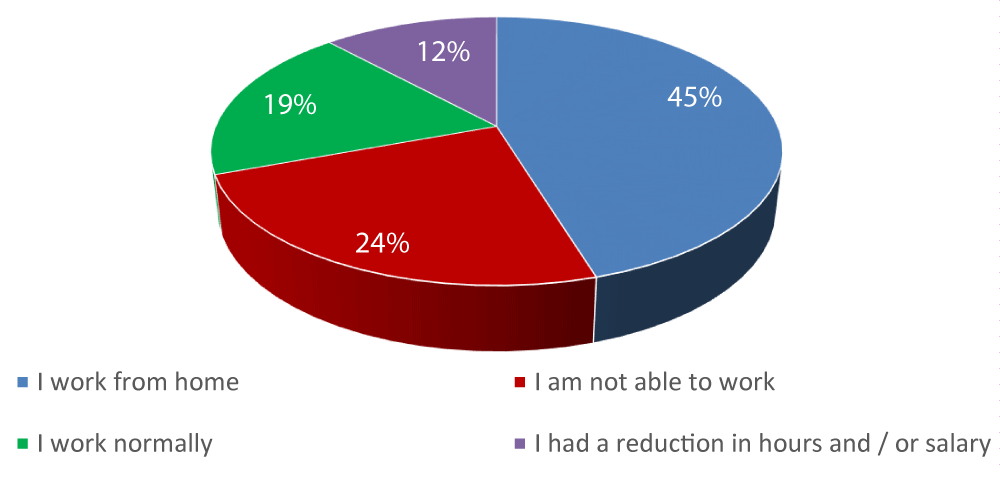

When comparing the financial situation before and during isolation, 69% of the respondents considered having a financial situation “Somewhat worse,” “Worse” or “Much worse” during isolation. The remaining 28% mentioned having the same financial situation as before the isolation. A similar result was found by Laguna et al., where the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the economy showed relevance during the period studied [5]. This is related to the change in the employment status of the respondents during isolation, where only 19% of the respondents had no changes in their employment situation. The rest had to modify their routine work, and 36% of it affected its economy due to salary reductions or being unable to work. Figure 1 shows this situation.

Figure 1: Employment status of respondents during lockdown; expressed in percentage of mentions.

Eating habits

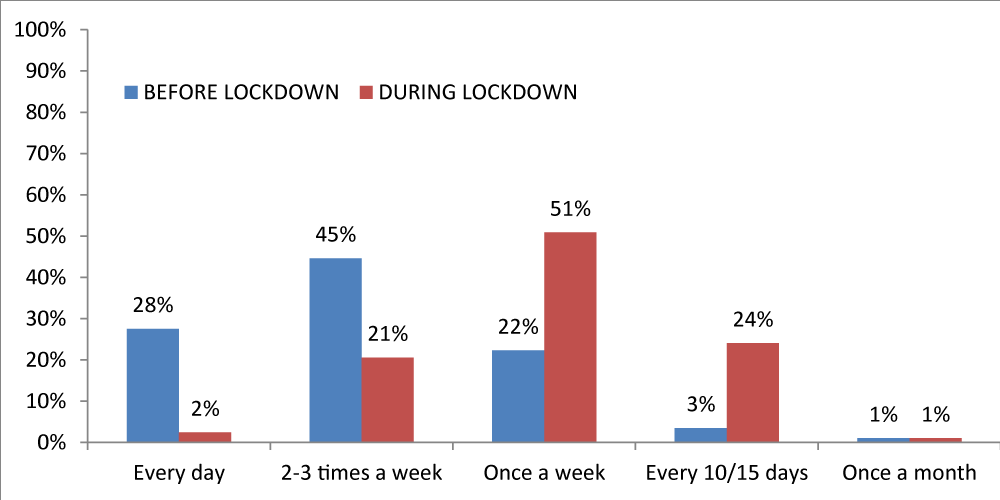

During isolation, the frequency of purchases decreased. Before isolation, the most mentioned frequency was “2 to 3 times a week” (45%), followed by “every day” (28%), while during isolation, 51% made purchases “once a week” and 24% “every 10 or 15 days” (Figure 2). Similar results reported Laguna, et al., where the consumer’s frequency of shopping was Twice per week (50%) or Weekly (35%) before the lockdown. After the lockdown was Weekly (76.5%) and Twice per week (13.65%) [5].

Figure 2: Food shopping frequency before and during de COVID-19 lockdown, expressed in percentages of mentions of each frequency

As in Laguna, et al. [5], no changes were observed in the places chosen to make purchases before and during isolation. 60% did not buy food excessively because they did not fear shortages. In contrast, Italians “assaulted” supermarkets in the hope of gaining comfort and a sense of control in a situation of total anxiety and uncertainty [7].

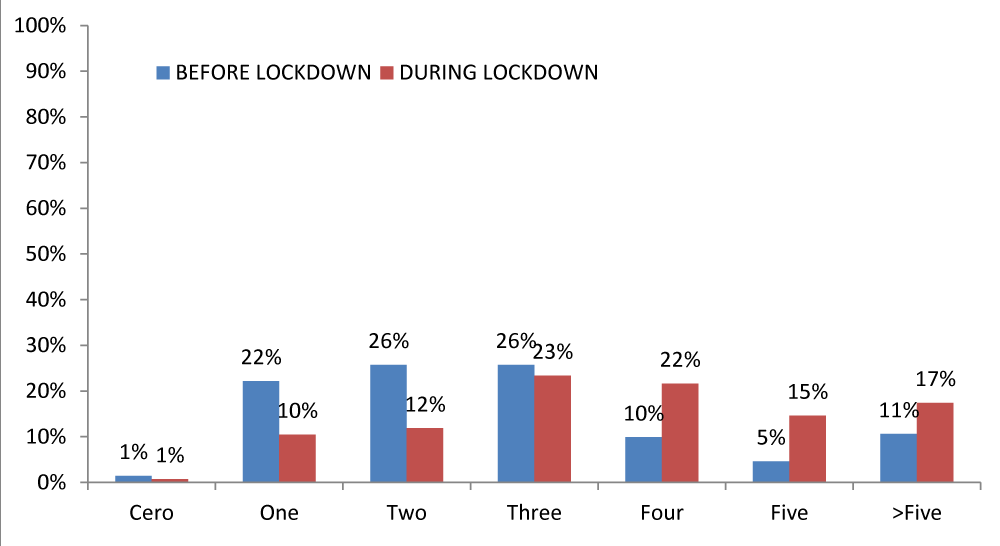

Bracale and Vaccaro observed a strong reduction in the sales of fresh goods, such as fruit and vegetables. In our study, this change was not observed; between 37% - 41% of the 9 de Julio populations consumed these foods more than 5 times a week in both situations (before and during lockdown). However, changes were observed in the consumption of pasta, bread and cakes; Figure 3 shows the consumption of these foods before and during the lockdown. This category of products was also increased in other studies [1,5].

Figure 3: Pastas, baked products and cakes consumption before and during de COVID-19 lockdown, expressed in percentages of mentions according to days a week.

According to Bracale and Vaccaro, the tendency to make bread, pizza and sweets at home, suggested by these consumption dynamics, could be interpreted as a pleasant way to spend time during a mandatory stay at home policy. Another possible reason is the effect of a positive reaction to boredom linked to the drastic reduction of activities and their routines [1].

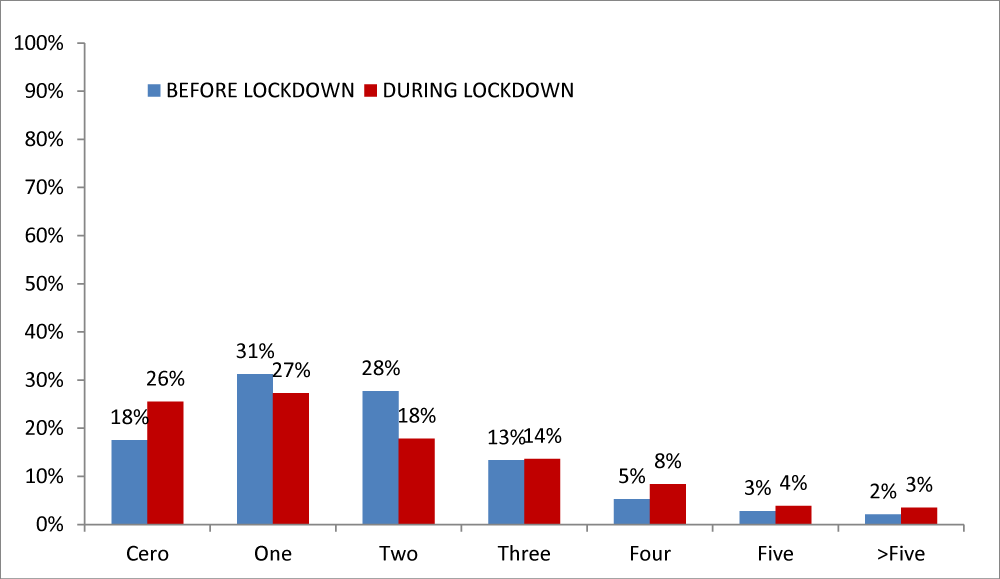

In agreement with Di Renzo, et al. [7], in our study the purchase of food by “delivery” decreased notably during isolation. This could be related to multiple factors such as distrust of ordering food in this pandemic situation, having more time to cook if working from home and due to economics. Furthermore, 53% fully agreed with the following statement: “By spending more time at home and being able to cook, I can eat healthier and better”. As well as, when respondents were asked about the consumption frequency of snacks, candies, ice-cream or fast food; frequency 1-2 times a week decreased a during isolation; also the frequency “never” increased from 18% to 26% during isolation. Figure 4 shows this behaviour; in general, the low consumption of these foods was observed too.

Figure 4: Consumption frequency of snacks, candies, ice-cream or fast food, before and during de COVID-19 lockdown; expressed in percentages of mentions of each frequency.

The consumption of alcohol was similar before and during isolation. Some studies reported in the literature support our findings [5] and others do not [1,7].

Considering the general difficulty of the moment and that the priorities are different, there are 55% of the people who consider that “The economic factor is crucial to eat healthy.” This is consistent with the fact that 70% consider that they had a healthy diet before isolation and that percentage decreased by 10%. The COVID-19 lockdown, for most those surveyed did not cause the lack of control in their usual diet. However, 39% agree with the phrase “When this situation ends, I will organise myself again with food”.

More than 50% considered that their diet is “close” to the ideal diet, both before and during the isolation and 56% fully agree that “Even in this situation, I could eat better.”

The perception of weight before and during the COVID-19 lockdown was considered. More than half of respondents (58%) declared being “a bit overweight” before the lockdown; this percentage increased slightly during the lockdown (64%). A more pronounced finding was presented by Di Renzo et al. they concluded that, during the COVID-19 lockdown, the perception of weight gain was observed in 48.6% of the Italian population [7].

Physical activity

Concerning the physical activity, approximately 70% declared to train before the COVID-19 lockdown, decreased by 13% during the lockdown. This decrease could be due to the lockdown governments that prohibited the great majority of outdoor exercise and social activities (e.g., going to the gym), reducing the physical activity; this restriction also happened in our city. To highlight, such as in the result of Di Renzo, et al. [7],

the percentage of people who mentioned doing physical activity more than 5 times a week during isolation doubled. The most important reasons indicated by the respondents about doing physical activity before and during the COVID-19 lockdown were “physical health” (80% both before and during the lockdown) and “mental health” (68% before and 76% during the lockdown, respectively). Other reasons for doing physical activity, mentioned less frequently, were: “because I like it”, “because entertain me and calms my anxiety”.

On the other hand, the respondents were asked about what activities or skills they developed during the lockdown. The most mentioned activities were cleaning the house, cooking, watching television, series and movies. Table 1 shows the percentage of mentions of these activities. The high percentage of mentions observed in the activity “cleaning the house” could be due to that domestic service was suspended during isolation; and so, this task had to be done by ourselves. All the activities listed in table 1 were totally associated with the respondent spending more time at home.

| Table 1: Activities and skills developed during the COVID-19 lockdown. | |

| Activities | Percentage (%)* |

| Housecleaning | 71 |

| Cooking | 69 |

| Watching TV, Series and Movies | 60 |

| Social network | 50 |

| House fixes | 39 |

| Reading | 36 |

| Studying | 32 |

| Handcrafts | 26 |

| *The percentage gives more than 100 because the answers were not exclusive. | |

Concepts and emotions associated with isolation

A percentage greater than 50% of the surveyed population associated the situation of lockdown with positive emotions (share with the family, stay at home); while only 24% associate it with negative emotions (anxiety, anguish, fear).

Concerning the concept “My anxiety influences my usual way of eating,” the opinions were divided; 42% of the surveyed population did not agree with this sentence and a similar percentage (43%) agreed with this sentence.

Concerning the concept “Eating in these circumstances distress me”, 69% of the surveyed population did not agree with this sentence, and only 15% of the subjects agreed. Similar results were observed in the concept “Eating in these circumstances relaxes me”, where 51% of the surveyed population did not agree with this sentence, and 29% of the subjects agreed.

At the end of the questionnaire, the respondents spontaneously wrote the first 3 sentences associated with this situation. Different concepts, emotions, ideas or thoughts emerged from this question, and these were grouped in categories; those with the highest mention are listed below:

- Return to normality: I need to get back to my routine, I want it to end soon, I am tired of the lockdown.

- Situation that will generate change: learnings, discoveries, social and eating habits, etc.

- Alterations in eating habits (diet): sometimes for the better (I have more time to cook, so I avoid rotisserie food, I have more time at home, this helps to prepare healthier food); and sometimes for the worse (My need for flour increased, I am eating six or seven times a day, this is much more than usual).

- Negative emotions: sadness, nostalgia, missing (I am sad because I miss my freedom, being able to be with my family and friends).

- Economic concern: economic instability, price increases, decreases in wages, etc.

In this study, we have provided for the first-time data on lifestyle, eating habits and other habits during the COVID-19 lockdown in a small city far from the big urban centres.

It is expected that most habits will return to normal; however, it would be interesting to know which of those developed, adopted and implemented during lockdown will remain in the new normality.

Further studies are needed to investigate the long-lasting effects and adaptation of food consumption behaviour.

- Bracale R, Vaccaro CM. Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to Covid-19, Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases. 2020; 30: 1423 - 1426. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32600957/

- Vergara-Castañeda A, Díaz-Gay M, Lobato-Lastiri MF, Ayala-Moreno MR. Cambios en el comportamiento alimentario en la era del COVID-19. RELAIS. 2020; 3: 27-30.

- Muscogiuri G, Barrea L, Savastano S, Colao A. Nutritional recommendations for CoVID-19 quarantine. European J Clin Nutri. 2020; 74: 850-851. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32286533/

- Hunot C, Fildes A, Croker H, Llewellyn CH, Wardle J, et al. Appetitive traits and relationships with BMI in adults: Development of the Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Appetite. 2016; 105: 356-363. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27215837/

- Laguna L, Fiszman S, Puerta P, Chaya C, Tárrega A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual Prefer. 2020; 86: 104028. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7358165/

- Rodríguez-Martín BC, Meule A. Food craving: new contributions on its assessment, moderators, and consequences. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015; 6: 21. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4302707/

- Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, Soldati L, Attinà A, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID‑19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020; 18: 229. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32513197/